American Psychological Association

123rd Annual Convention

Toronto, Ontario (CA), August 7-10 2015

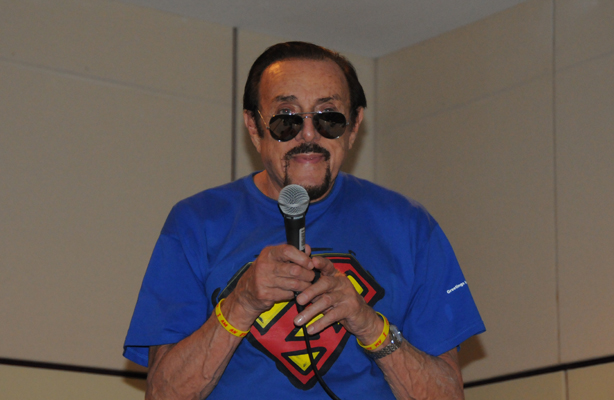

Phil Zimbardo and The Stanford Prison Experiment

Philip Zimbardo, Ph.D.

Dr. Phil Zimbardo, the legendary social psychologist who was the first to study 'shyness' in depth - and then went on to address the much different behavior seen in his famed 'Stanford Prison Experiment' - addressed the large audience which had just seen a screening of his newly-released movie about the prison study. Whereas last year Zimbardo began his presentation to the sound-track of 'Evil Ways' and spoke about the famed study and the imminent making of a film about it, today he showed up wearing his prison-guard sunglasses, and spoke with the many who had gathered to see the film and to now hear from the man himself, about his real-life experience as 'prison superintendent' and psychologist, and on his perspective regarding the movie depiction.

"I'm going to talk a little bit about what I liked about it - the movie - what I don't like about it, and then we'll open it to Q & A.

This movie has been 44 years in the making....

There have been many scripts, many directors, many actors who wanted to do this movie, and we've had many companies take options. And none of it worked. They wanted to over-dramatize it, they wanted the movie to be about Leonardo di Caprio in one version... The script writer for Usual Suspects, who's won an Oscar, wrote a script which was terrible. And so I had given up.

And then about 13 years ago, a producer from a little company in L.A., Coup d'Etats Films, said I want to make this film, I'm dedicated to it.... And then what he did was, he signed as a consultant a script writer, Tim Talbott. And fortunately for me, it was at the time I was writing The Lucifer Effect.

So as I was writing each chapter about the prison study within The Lucifer Effect book, I would send it to Tim Talbott. So in fact the original script was several hundred pages. A script for a movie has to be 30 to 40 pages.

So essentially all of the dialogue between prisoners and guards is accurate. Because in Lucifer Effect, what I did was I went back and looked at all the video, We had 12 hours of videos, and I made typescripts of them because I realized I had never written a book about the prison study... I wrote a few articles and put it to sleep... I started doing research on China, I started doing research on time perspective, I still am...

But I never wrote a book about it.

And then I was involved in defending one of the guards, one of the American guards, at Abu Ghraib.

And I realized Abu Ghraib was The Prison Study on steroids. No question about it. Everything in Abu Ghraib had been mimicked from the Prison study. Putting bags over prisoners' heads. Stripping them naked, sexually abusing them, etc.

And so, I said

let me go back and revisit that whole study and see what really happened, because, you know, there's memory distortion...

And then... instead of writing it as a memoir, this old thing, I wrote it in first person, present tense, because that's what the script is about.

So when John Wayne says to 416, 'you know what I'm going to do with those sausages, boy, if you don't eat them?' No sir, what're you going to do? ....

It's in my brain, and so I said 'that's what's going to make The Lucifer Effect interesting'. So again, almost all of this dialogue between prisoner and guard is accurate, it's from the prison study.

I was a consultant on the movie. I spent a couple of days on set with Billie Crudup and his people, playing his staff.

All the prisoner and guard shots were done in 2 intense weeks, in a studio in Burbank.

Now the other thing they did to make this movie so effective: They sent a whole production crew down to the basement of Jordan Hall, which is in the Psych Department where the study was done.

They made videos, they made measurements.

So in fact every detail of that basement is reproduced to the last millimeter. So it's identical. So when I'm on the set looking at the monitor of the original study and looking at the video of the current thing, I couldn't tell the difference. The only change was, they made the set so they could lift the roof off and have a camera go down, as you saw in some scenes, or the back of the cells ... they wanted to show what was happening, cell by cell. But other than that it's identical.

Even this subtle thing: There was only a single door going in and out of the prison, and

the Stanford psych department technician, in order to bolster the door he put a piece of wood this way, this way, that way. Which if you look at it, it was a 'Z'.

It was not meant to be a Z, but it was, and they have that in the movie.

So all of that was accurate.

What's not accurate?

Some of the things - they didn't have the money... This is a low-budget film. Two million bucks is not a lot... there were 24 actors, 24 young actors... people playing the role of parents, etc. etc. So it's a big, big cast. No money for uniforms...

Everybody's dressed in 1971 garb.

Everybody's got 1971 hair.

In those day everybody had hair.

There were some changes ... many scenes were cut. They actually shot 2 hours and three quarters. They had to eliminate 45 minutes. It's a long movie at two hours.

And so, sadly a lot of good stuff was cut. So for example, there were 9 prisoners arrested, you only saw one.

There were 7 prisoners who went to the parole board, You only saw one. There were 2 days of parents visiting - and by the way that took place on the yard, not in a separate place - [we wanted] the parents both to experience what their kids were experiencing, [and to] make the parents be a part of the study in a subtle way.

The parole board hearings were also done in a separate part of the building and I was never part of it. In fact we had secretaries, ordinary people, plus Carlo Prescott, who is this black ex-convict who has just gotten out of prison after 17 years. Sixteen of those years his parole was turned down by ... the parole board! So when he's now in that role - it's almost the most dramatic thing - He becomes somebody he has hated. For 17 years, that guy who he is, said 'no way, go back to your prison, come back next year'.

And so, here again, the whole movie is about the power of role-playing, that you start out playing a role and then over time you become the role, and the role becomes you.

So it's obvious in some of the guards, some of the prisoners - it's less obvious what happened to me.

But here's Carlo Prescott.

The priest is an interesting guy. In one way he contributed more than anything to convince the prisoners they were in a real jail.

Now he had been a prison chaplain in a prison in Washington, D.C.

During summer school, before the study, in July, I taught a course with Carlo Prescott, on the psychology of imprisonment, for undergraduates and graduate students at Stanford, in order for me to learn about prisons. We had ex-cons come in, we had guards come in, and other people. And this priest was there and he said, 'hey, I was a .... prison chaplain'.

He wanted me to give him some references. And I said, 'tradeoff!'. I'll give you what you need but I want you to come down to our prison and give me a sense of how realistic it is. Come down to our experiment.

And what does he do? Exactly what you saw. He knows it's an experiment, and what does he tell the kids? 'What are you doing to get out ?' 'What do you mean?'

... 'What's your charge?' Almost all the kids said what the cop had told them: 'violation of penal code 459 ...' And he says, 'What are you doing to get out?' He [prisoner] says 'What do you mean?'

And he says, 'You're in jail, you're in prison! You've got to get a lawyer to get out. Don't you know that? You should know that. You're a college student.' He starts humiliating them. And he says 'o.k., I'll get a lawyer'.

And one of the kids says, 'my cousin is a public defender. Please call my mother to contact him to help me get out.'

What does he do? He now is in the role of prison chaplain, and he calls the mother to say 'your son is in the Stanford Prison Jail, and he needs a public defender to get him out'.

What you don't see in the movie is, on the last day the public defender comes down - and he knows it's an experiment, I briefed him. But

he goes in, and now there's only 5 kids left (including his cousin), and he goes through the public defender's routine: Have there been promises not kept, have there been threats? Has there been inadequate diet? He goes through the checklist.

At the end he says, 'OK, I'll be back on Monday'.

And the kids start screaming. 'Monday?! We can't live another day, you've got to get us out!'

He says,

I'm a public defender, I'm not a lawyer, I can't get you out.

The kids start yelling and crying, and that's the point at which [raps on the wood podium 3 times]

the study is over. So that's how it ended.

Back up to the night before.

You saw the confrontation I had - that Billy Crudup had with Olivia Thirlby.

That was me and my girlfriend, Christina Maslach.

What they cut out, unfortunately for women's heroism, is the line in which she says 'You have become somebody I don't know. The situation has changed you, not just the prison guards...

How could you see the suffering I see and not be upset?' Then she said, 'I know you as a loving, caring person. Students love you... But something has happened and you've changed. And if this is the real you I want to break off our relationship.'

Now you saw in the movie, we had just moved in together, in San Francisco - 1725 Taylor Street - and we're planning on eventually getting married and having kids... And she says, 'this is wrong. I'm willing to give up all of that for a moral cause.' She never said 'you should end the study'. She just said, 'Think about what you're doing. You're allowing suffering to go on.' For me, I'm saying, 'well, I prevented physical abuse.' The guards never hit prisoners. That opening scene is wrong, where a guard hit a prisoner. The only physical abuse was during the rebellion, when the guards broke in and the prisoners started attacking them. But after that I said, No physical abuse.

But I didn't prevent psychological abuse, which over time is much worse.

Namely the guards created a totally arbitrary environment, in which the

guard would tell a joke and [if] you laughed, you got punished. Guard would tell a joke and you didn't laugh, you got punished.

So aside from the kids who broke down - and there were 5, they only showed a few - the other kids became zombies.

No matter what the guards said, they did it:

'Tell him he's an a**hole'. 'Spit in his face' [They'd do it.]

So for the kids that broke down, this was a way of getting out.

In fact, after 8612 broke down and got out,

that was a negative role model, how you get out of this study.

Now what's interesting is, if any prisoner said 'I want to quit the experiment', that was the magic phrase. I would have had to let them go, because that's what I had agreed with the human subjects committee.

In 1971 there was a human subjects committee that approved the ethics of that study. So if people say, is that study ethical? Of course it is! Because before you did it, what was it, it was kids playing cops and robbers in the basement of the psychology department, in an experiment, and everybody knew it was an

experiment; they signed informed consent.

After the fact they say, 'how can anybody allow that?'

In fact the human subjects committee said two things:

You have to make student health aware of it in case a kid got sick.

And also, there's only one entrance, so it could be a fire hazard, so there were fire extinguishers the guards used on the prisoners.

(That's not what the ethics committee thought.)

So backing up now...

One of the ways I knew to make The Prison Study work, is having the police arrest the prisoners. Because you needed the authorities to take away your freedom. If they had come and said 'I'm here for the study, to be in your experiment, I'm going to be a prisoner or a guard', once we assign them to be a prisoner, when [things] got bad they'd say, 'I take back my freedom. I gave it to you, I can get it back'.

But now the authorities took it away. The police arrested you. They charged you with a crime.

And what they didn't show, sadly, in the movie - because they didn't have the budget:

The police took each kid to the real police station in Palo Alto.

They had a full booking - fingerprinting, photographing,

put them in a real jail cell.

One after another.

And then Craig Haney and Curt Banks, my assistants, picked them up and blindfolded them, and brought them to our prison. And then you saw the prison initiation.

And they did that with

kid after kid after kid.

So even though they knew they had not done what the police had said

when they read them their Miranda rights, nevertheless the authorities took away their freedom.

and only the authorities, namely the parole board, could give it back.

In fact, at the end of each parole hearing, each prisoner was asked, 'Would you be willing to forfeit all the money you have earned as a prisoner if we were to parole you?'

Everyone said yes.

We're surrounded by secretaries - they just said what? 'I don't want your money'. The only reason any of them were in the experiment was for the 50 bucks a day - not to be in a prison study!

They had just finished summer school at Berkely and Stanford [and Santa Cruz State] ... These are kids from all over the United States. [Only two were Stanford students. It's a little misleading: Only one guard and one prisoner were from Stanford.]

At that point what should they have done? They should have said, 'I'm out of here!' I don't want your money, I'm out!'

Instead, the head of the parole board calls and says 'take them away'. They stand up, put their hands out like this [arms extended], the guards put handcuffs on,

bags over their heads, takes them away.

At that moment it was no longer an experiment, it was a prison. As one of the prisoners said, it was a prison run by psychologists.

So in fact one of the lessons is the extent to which all prisons are prisons of the mind.

Shyness

And so when I finished this study the first thing I started studying was: shyness.

Shyness is a self-imposed psychological prison!

Nobody says 'you're shy'. You say 'I'm shy. Therefore, I can't ask a girl for a date,

I can't answer the question even though I know the answer, I can't ask for a raise even though I deserve it... And then you become your own guard who limits your freedom: freedom of association, freedom of speech... In your own prison you'll be locked in with yourself.

So with that metaphor I went on to study shyness, for the next 20 years.

I was the first person to study shyness beyond adolescence. And then we created a shyness clinic which is still in effect in Palo Alto University where I taught for a number of years. Then I wrote a book called 'Shyness: What It Is, What To Do About It'. It sold 500,000 copies to ordinary people.

So for me, that's my legacy, not this. [Extending an idea, translating it into research...] We did cross-cultural research, laboratory research, survey research. Translated that into practice, Creating a therapy for shyness which works 100% of the time. And then presenting your ideas to the general public. For me, that's what I want to be remembered for rather than ... this bad [$h!*]. (laughter)

Perspectives on the Movie Portrayal

So Billie Crudup does a pretty good job of being me, with one big exception: He doesn't understand what it means to be an academic professor working with graduate students. His model is really a European professor who is very formal. He's formal: the way he stands, the way he moves. He never touches his students, you see ... Again, you know, I'm Italian, I'm Sicilian: I'm hugging myself, [making hand gestures] all the time... and making jokes. And if you're a research professor your life depends on your relationship with your students. There are students I worked with 20-30-40 years ago, when I meet them, we're still comrades. And there's none of that.

And because there's none of that you don't see a change in him as much. He's too negative too early. Except for the opening scenes where he's loving with his girlfriend Christina, he's too negative. And I tried to tell him that on the set and also I tried to tell him, 'Billy, I'm a Sicilian! Billy!' [gestures] He couldn't do it! Because actors are paid to not have their hands come in front of their face.

So for me that's a weakness. It's not enough of a psychological transformation of being the objective, neutral, distant researcher who then

gets sucked into his study and at some point becomes the prison superintendent.

For me the key scene - and again, it's not dealt with as well as it could be - is visiting night ... The kids looked really ragged, I mean worse than the actors did, because our prisoners are being woken up every 2 hours. They had bags under their eyes, they were groggy, they had insomnia.

And Mrs. [x] & and Mr. [x] come in, because at the end of visiting they had to see the prison superintendent. I was in the office that said 'Prison Superintendent'.

'Dr. Zimbardo', the mother says, 'I don't mean to make trouble but I've never seen my son looking so terrible.'

Red light! She just said 'I don't mean to make trouble'. She's going to blow the whistle, and I should look out. So what am I going to do? I could say 'tell me a little more' or I could say - what? 'What's your son's problem?'

This is every administrator.

You know, when the teacher gets a kid, and the mother comes in, the teacher always says,'why is your son so uncontrollable?'

And so you put them on the defensive.

So she says, 'He's so tired, he doesn't sleep.'

I say, 'does he have insomnia'?

What am I doing? I'm saying 'the problem is your son'.

The whole study is the study of power situations over disposition.

What I'm doing is saying 'what's your son's disposition?'

'He says oh, they wake us up at all hours of the night.'

>

Oh yes! We call those 'counts'. The guards on every shift have to account for the fact there hasn't been an escape.

And she says one more time, near the end of the movie, 'I don't mean to make trouble'.

She's going to blow the whistle!

So what am I going to do? I'm going to become a sexist. That's a role that I hate.

What does that mean? I'm going to turn to Dad and say, 'don't you think your son is man enough?'

What is he going to say to himself? 'Oh no, he's a real ...' So I give him a high 5, with a guy shake, have fun guy, and he says 'See you next week'.

At that moment we cut the mother out. It's a 'guy thing'.

That night a kid broke down. That night she sent me a letter, which I have in The Lucifer Effect. Saying 'you're doing such good work, I'm really sorry to make trouble...

But she was right on. And the father who saw the same kid was

seduced by this sexist role.

And after the fact, when I saw the video of that I was horrified. Oh my God, how could you do that? That was, for me, slipping into the role of prison Superintendent.

The other thing was... The worst scene in the movie is the gym scene. They just got it wrong...

What happened was, we believed the rumor - namely 8612 was going to break in with his buddies to 'liberate the prison'.

8612- with all of that rhetoric... He had been a student activist at Berkely, against the Vietnam War. And what they did was they broke windows in the library, and he police came and he ran away. So now again he was 'power to the people'.

But now, he couldn't run away.

....The guards knew how to break any kind of prisoners' alliances by punishing the other prisoners. So the rumor was he's going to break in. And we believed it.

So the first thing I did,

which was really crazy,

I called the sergeant and

I arranged a squad car for us... And I said 'I have a prison break on my hands. I need your help... I want to bring back all the prisoners to the Old jail.' [We have the prisoners all lined up ...] We're about to bring them to the old jail, and he calls and said, 'the city manager

says we can't do it: it would be an insurance liability'...

I said, I've got to come down. I go down, 'We need your cooperation! There's going to be a riot!'

He must have thought I was a *$#@! lunatic! (laughter)

I say, 'Where's our institutional cooperation?' Anyway... So that was out.

So then the plan was, we dismantle the whole prison, take the doors off, beds in the hall, and I'll sit there. And when they break in I'm going to say 'too late, nothing was happening, the study is over, go home', and then that night we would reinforce the doors and everything.

,

It was a rumor! I studied rumor transmission! I should have been studying rumor transmission... instead we believed it.

So I'm sitting there waiting for this momentous event. And in comes my Yale graduate school roommate, ... We're colleagues at Stanford. And so he's my age. I say, Gordon, I've got a big problem on my hands, I'll talk to you another time! And he says joshingly, 'Hey, what's the independent variable?' And again I say, of course, 'random assignment of prisoners and guards, now get out of here!' What they do in the movie is have this old guy come in and make the young guy look foolish. I don't even know if he ever answers the question and I don't know why they did that. But it's one of the few bad directorial pieces. Other than that the directing is really, really good... And the director Kyle Alvarez did all the editing...the editing won an award at Sundance.

I would say it's about, probably, 90% accurate, 90% of the scenes. All the dialogue between prisoners and guards is right on. I don't use obscenities, I only use sh**. A lot of the obscenity ... is part of the R rating, plus you see 8612's butt. (laughter)

What I'm trying to do now, is...

The study premiered in New York and then Los Angeles. And during that time

the President of the United States, Barack Obama, visited a prison.

Believe it or not he is the first President of the United States in 200 years to visit a prison.

No President ever visited a prison, not a federal or state prison, and so it made news. And then he said,

'We must now engage in prison reform'. Because prisons now - there are

2.3 million American citizens in prison.

When we did the study in '71 it was about 700,000 and I was complaining that was too much. Of those a huge number are

African-American men, Latino men, there for non-violent crimes, for drug crimes. And it's costing us billions of dollars in tax support.

The other thing that's happened is, prisons have become privatized,

meaning: there are companies making money on keeping prisoners in prison. With no rehabilitation...

So essentially what I'm trying to do is have a showing of this study at the White House, for 2 reasons:

When we premiered the movie in New York, Obama's daughter Malik put on Twitter that she and her girlfriends saw the movie and liked it.

And secondly, President Obama's primary assistant is Valerie [Jarrett?]... who was my honor student at Stanford, [so I've been writing to her saying come on Valerie, show the movie, I'll come down and we'll get the President behind it. That would be really good.]

So essentially, what's the 'message' of The Prison Study?

Purposely the director chose not to make it didactic - not to make the actors say, 'and this study shows the power of social situations that dominate individual personality, the importance of understanding systems...'

He decided not to do that, not to have any of those 'educational messages'.

The idea is to make the movie sufficiently riveting, fascinating, emotionally expressive, that it would promote self-reflection.

What kind of guard would I have been? What kind of prisoner? If I was the superintendent would I have allowed this to go on as long as it did? Why didn't you end it after the 2nd prisoner broke down?

We can switch the roles. The guards could have become prisoners, the prisoners could be the guards, like Jane Elliot's Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes.

So the idea is we want this to stimulate those kinds of conversations.

How is this different than the Milgram study?'

Incidentally, little Stanley Milgram and I were in the same class at James Monroe High School in the Bronx in 1950. We drank from the same Bronx polluted water. [laughter]

For me these are the main things... I'm going to write a thing, 'Reality Departures', to say: Here's what was accurate in the movie, here's what they did there.... I'm trying to get the director to do a director's cut, but he's somebody that doesn't believe in that. He's got 45 minutes that he cut out that I'd like him to put back..."

With that [as time was running out] Dr. Zimbardo invited questions.

Q & A

QUESTION: I'm an undergraduate student from Los Angeles... My question is, how did you take this negative and turn it into a positive?

A: Well, thank you. That's a great question. Actually, in 2007 or 8, I gave a conference at the TED conference in Monterey and it was really my journey from creating evil - which I did - to now inspiring heroism. Inspiring heroism, it's just the thought to say: Ordinary people could become everyday heroes. I wanted to get away from the idea of military male warriors - Agamemnon, Achilles... Anybody can be a hero, through deeds of daily kindness, through being socially focused. And at the end of that conference many people came up ... and said 'hey, you should have a foundation. You should promote this hero stuff - because nobody ever talks about that.']

And in fact, two things missing from every psychology textbook, including all of Marty Seligman's 'positive psychology', are the words 'hero' and 'heroism'. Doesn't exist.

[How is this entirely missing] from psychology's lexicon... even in 'positive psychology'? Marty Seligman says: it's not a private virtue. Compassion is there, empathy is there. Heroism is but a civic action.

And I say 'what good is compassion and empathy if it doesn't lead to civic action? It makes you feel good; it doesn't change the world.'

So essentially what I did is, I created, in San Francisco, a non-profit called the Heroic Imagination Project. It's online: HeroicImagination.org

And it's to teach ordinary people, especially young kids, how to be everyday heroes, how to be heroes in training.

Essentially we have developed over 6 years a number of unique educational programs - on bystanders,

on mindset, on prejudice - which are revolutionary because teachers no longer lecture, teachers are like coaches. And all of our

lessons are built around videos because kids live in a visual world.

So our program now is in many schools in California, all over Hungary, Poland, and in the Godfather town of Corleone, Sicily.

We need sponsors, we need volunteers....

[More information: heroicimagination.org]

See also:

Zimbardo on Transforming Evil into Heroism (2014)

Zimbardo: Analysis of a TED Event (2012)

Zimbardo: Reflections (2011)

Enduring Lessons from 40 Years Ago: Stanford Prison Experiment (2011)

Q&A with Zimbardo (2009)

Evil, Hate, & Horror (2007) - Zimbardo and Beck

![[color line]](http://www.fenichel.com/moveline.gif)

2015 APA Convention Highlights:

Aaron T. Beck at 94: Humanism, Therapy, and Schizophrenia

| Albert Bandura: Efficacy, Agency, & Moral Disengagement

| Danny Wedding: Psychopathology & Psychotherapy in the Movies | Phil Zimbardo on 'Stanford Prison Experiment' (the movie)

2009 Convention Highlights:

Internet: Pathway for Networking, Connecting, and Addiction | Opening | Virtual Psychology & Therapy | Q&A with Zimbardo | Seligman: Positive Education | Future of Internet Media | Sex, Love, & Psychology | How Dogs Think

2010 Convention Highlights:

Online Support Groups & Applications |

Evidence & Ethical Practice | Opening Ceremony | Sir Michael Rutter: Resilience

Group Memory | Psychology in the Digital Age | Steven Hayes: What Psychotherapists Have that the World Needs Now

[TOP]

![[color line]](http://www.fenichel.com/moveline.gif)

![[Current Topics in Psychology]](http://www.psychservices.com/CTparent.jpg)

![[Back]](http://www.fenichel.com/back.gif) CURRENT TOPICS in PSYCHOLOGY Q&A Teaching Tools APA 2000 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

CURRENT TOPICS in PSYCHOLOGY Q&A Teaching Tools APA 2000 2001 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Copyright © 2015 Michael Fenichel

Last Updated: Saturday, 29-Aug-2015 01:45:42 EDT

![[Current Topics in Psychology]](http://www.psychservices.com/CTparent.jpg)